A Neurosurgeon’s Unexpected Joy

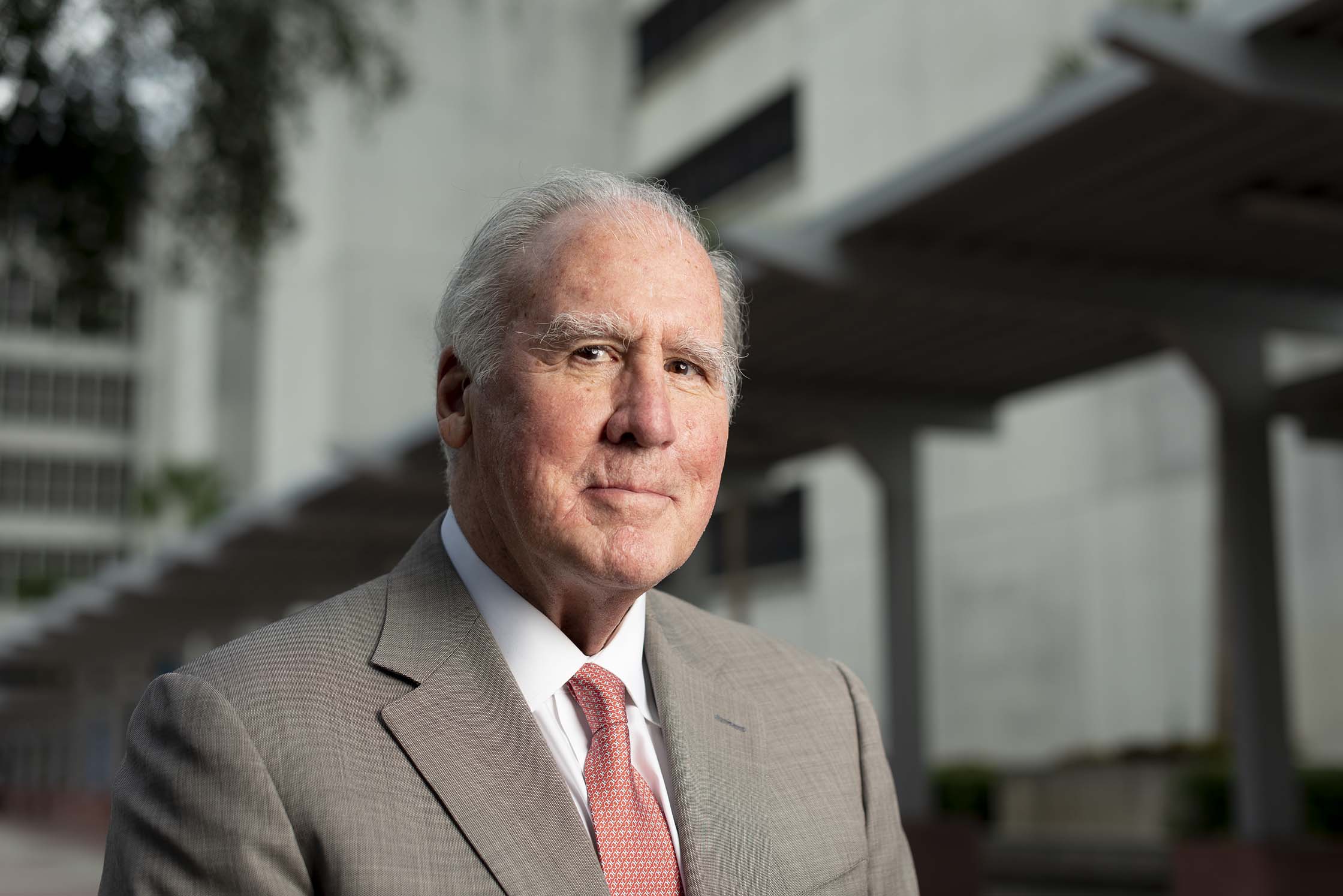

Dr. Roberto Heros says that empathy is essential for any physician and why some patients remember you decades later

By Bob Woods

Photograph by Tom Salyer

Dr. Roberto Heros says that empathy is essential for any physician and why some patients remember you decades later

L

ast December, Roberto Heros, M.D., received a letter from a former patient, thanking him for performing successful spine surgery — in 1984. “You may not remember me, but I cannot ever forget you,” the patient wrote.

The letter prompted Dr. Heros — who recently turned 80 and is retired as a neurosurgeon but who still serves as chief medical administrative officer for Jackson Health System — to reflect on his long career and the “rewards of seeing patients get better.” But before recalling his medical education, nearly two decades practicing and teaching in Boston and Minneapolis, and then moving to the Miller School in 1995 as a professor, Dr. Heros told the incredible backstory that circuitously led him to neurosurgery.

“I grew up in Havana, Cuba. My father was a pediatrician, and my uncle was a neurosurgeon,” he said. As a child, he would follow his uncle around the hospital, carry his medical bag and see patients with him. “That was clearly my inspiration for neurosurgery,” he said.

Next came what Dr. Heros called “a little bit of a complicated history.” His family fled Cuba in 1960, a year after the Castro regime began, and settled in Miami. At 18, Heros trained as a paratrooper and with fellow exiles participated in the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, the ill-fated attempt to overthrow Castro. Heros was captured and spent two years in a prisoner-of-war camp.

“It didn’t look probable that I was going to become a neurosurgeon,” he said of his time as a POW, “but things worked out well, and eventually I followed my dream.”

Today, Dr. Heros fondly remembers scores of other satisfied patients, incredible advances in neurosurgery and training hundreds of neurosurgery residents. Ironically, though, he cited the patients whose surgeries did not go well as his most enduring memories. “I found through the years that, remarkably enough, some of the people whose outcomes were the worst became some of the most grateful patients,” he said. The reason, Dr. Heros surmised, is “they can tell I suffered along with them and they were trying to make me feel better.” In fact, one of those patients for years sent him a Christmas card, and another brought him boxes of Cuban cigars.

Empathy for every patient, regardless of outcomes, is an essential attribute for any physician. But when it comes back around, that’s joyful. ![]()