Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center is a leader in bringing diversity to clinical trials

By Ana Veciana-Suarez

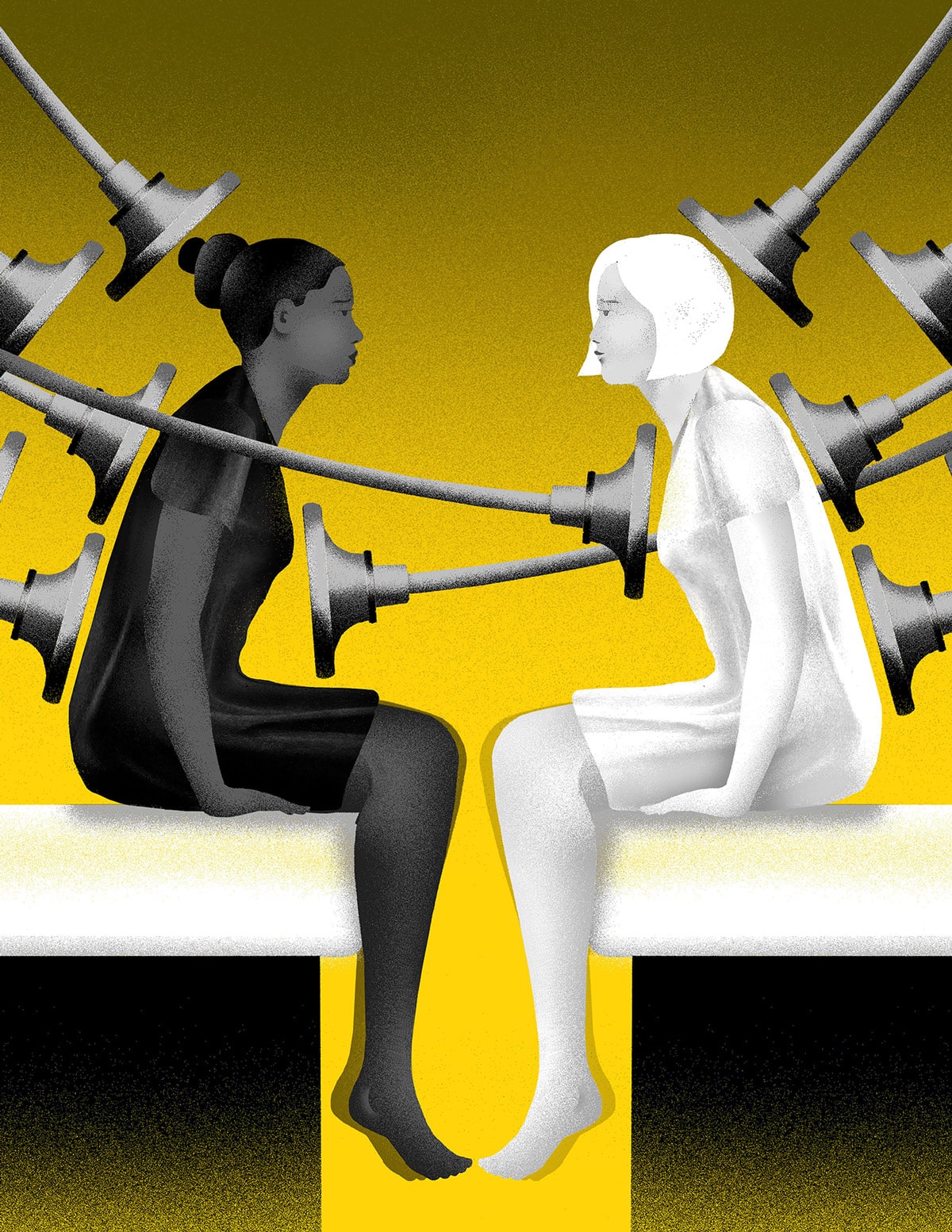

Illustrations by Brian Stauffer

imely screening, cutting-edge therapy and widespread health care messaging have made a dent in cancer mortality rates in the United States. This, however, isn’t true for all communities.

imely screening, cutting-edge therapy and widespread health care messaging have made a dent in cancer mortality rates in the United States. This, however, isn’t true for all communities.

Though cancer is an equal-opportunity disease, some groups shoulder a disproportionate burden. The reasons ethnic and racial minorities are at increased risk of developing — and dying from — certain cancers are many: genetics, of course, but economic, environmental, even educational and psychosocial factors also come into play. It’s no surprise that society’s inequities are reflected in our health care system.

At Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, physician-scientists are studying why certain populations are unevenly affected by particular cancers. This effort is part of a concerted, system-wide mission to level the playing field.

“Achieving health equity is a goal for most scientists and clinicians in cancer research,” said Erin Kobetz, Ph.D., M.P.H, vice provost for research at the University of Miami. “But at Sylvester, it’s an integral part of our mission. It’s part of who we are.”

Dr. Kobetz believes Sylvester is uniquely situated to be a leader in this mission. As part of the Miller School of Medicine, it makes its home in a geographic area with large Hispanic and Black populations. South Florida is also a gateway for people coming from Latin America, the Caribbean and Europe, and it can claim an impressive diversity along ethnic, sexual and socioeconomic lines.

“We are the future demographic of the U.S.,” Dr. Kobetz added. “We are truly well positioned to ask questions today that the rest of the nation will likely not even be able to conceptualize until future tomorrows.”

A Strong Commitment to Community Outreach

Achieving racial health equity requires being integrated into the community at every level, notes Sylvester Director Stephen D. Nimer, M.D.

“A critical part of our mission is to serve the most vulnerable,” he said. “To best address the most diverse needs of our community we have spent decades engaging stakeholders as partners. We have also established infrastructure capable of providing access to world-class doctors for everyone. We are committed to impactful and groundbreaking research, and we significantly invest in the education of students, faculty, patients and caregivers.”

When the National Cancer Institute named Sylvester one of the nation’s top cancer centers in 2019, the prestigious designation noted its pioneering programs that seek to increase screening, detection and treatment of cancer in underserved populations. Its physician-scientists are aware that health equity can only be achieved by a strong commitment to community outreach, explained Sylvester medical oncologist Jonathan Trent, M.D., Ph.D. This includes education, screening, research, clinical care and survivorship.

“We try to break down the barriers any way we can,” he said.

ne step in the long journey to health equity is the inclusion of more minorities in clinical trials, an essential rung in the complex stairway of developing therapies and drugs for treatments. Last year, Sylvester was one of only eight NCI-designated centers picked to be part of a nationwide initiative to increase minority access to investigational targeted cancer therapy. It received a one-year, $550,000 grant because it had demonstrated “robust ability to accrue minority/underserved populations.” In other words, Sylvester has been a leader in providing cutting-edge clinical trials to South Florida patients from diverse backgrounds, said Dr. Trent, who is one of the project leaders.

ne step in the long journey to health equity is the inclusion of more minorities in clinical trials, an essential rung in the complex stairway of developing therapies and drugs for treatments. Last year, Sylvester was one of only eight NCI-designated centers picked to be part of a nationwide initiative to increase minority access to investigational targeted cancer therapy. It received a one-year, $550,000 grant because it had demonstrated “robust ability to accrue minority/underserved populations.” In other words, Sylvester has been a leader in providing cutting-edge clinical trials to South Florida patients from diverse backgrounds, said Dr. Trent, who is one of the project leaders.

The program, known as CATCH-UP.2020 (Create Access to Targeted Cancer Therapy for Underserved Populations), requires that at least half of the patients in these sponsored trials belong to a minority demographic. It’s one way to deliver promising early therapies to those who might otherwise not get them.

“It allows us to open early phase clinical trials to our communities,” said Dr. Trent, who spearheaded the grant application. “Many of these are available only in a very select number of NCI centers.” (There are currently 49 studies in the CATCH-UP.2020 clinical trial portfolio for patients with solid tumors and blood malignancies.)

But long before the CATCH-UP.2020 grant, Sylvester had a history of collaboration with key community partners, a robust program of community outreach and a long-standing community advisory board. For example, in 2004 Dr. Kobetz founded Patnè en Aksyon (Partners in Action), which brings together Sylvester and community-based organizations in Little Haiti to alleviate the high rate of breast cancer mortality experienced by Haitian American women living in the Miami metropolitan area.

Clinical Trials Lead to Changes in Screening and Care

As Sylvester’s associate director for clinical research and director of the carcinoma program, Dr. Trent oversees hundreds of clinical trials, many of which have led to changes in screening guidelines and care delivery. Among those are a series of trials led by Sylvester breast oncologist Judith Hurley, M.D., and molecular geneticist Sophia George, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences.

Working with researchers in the Caribbean, the Hurley-George team found that more than 25% of Black Caribbean women with breast cancer had mutations in one of two genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2. In comparison, these mutations account for less than 5% of breast cancer cases in the general U.S. population.

They also discovered that Caribbean women with breast cancer mutations developed the disease early and that these mutations actually varied from island to island. Their work ushered in improved guidelines for breast cancer screenings for women of Bahamian descent: Now, women of Bahamian descent with a first-degree relative with breast cancer are told to begin breast cancer screening in their mid-20s, instead of in their 40s.

Dr. Hurley began her research into breast cancer disparity in 2002, when she noticed that many of her Bahamian patients were presenting at a much younger age than her other patients. In fact, breast cancer is the leading cause of death in Caribbean women, and this is particularly important because at least 10% of the Black population in the U.S. is comprised of Caribbean Americans, with pockets of high concentration in certain metro areas, including South Florida.

“Their health problems are our health problems,” Dr. Hurley said. “When you move to a new country, you bring your genes with you.” She noted that half of Miami’s Black breast cancer patients hail from the Caribbean.

For Dr. George, understanding the why of this disparity spoke to her as a Black woman herself. And as a scientist and a member of the global community, “we want to make sure everyone has equal access,” she said. “That’s why we do what we do. We see people hurting, and we want to do something about it.”

Treating Patients Who Are Younger and Sicker

Like Dr. Hurley, Patricia Jones, M.D., M.S.C.R., a Sylvester hepatologist, noticed that her Black patients tended to be younger and that their liver cancer was at a more advanced stage when they came to her office. This resulted in a higher percentage of them dying. She seized the opportunity to launch studies, which unveiled a troubling reality: Race was the biggest predictor of death from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

Dr. Jones and her team also found that hepatitis B (HBV) — which is the leading cause of liver cancer — affected African Americans and Haitians more than other groups, yet they were the least likely to receive a life-saving transplant. What’s more, only a fraction of these patients were aware they had this chronic infection, and therefore had little knowledge that a vaccine could prevent HBV and that antiviral therapy can treat it.

“We need to meet people where they are,” Dr. Jones said. “We need to be flexible in how we get our message out and in how we deliver care. We’re not going to get anywhere if we can’t reach people in a way that is sensitive to their culture and in a way they understand.”

As part of its work, the Jones team reached out to Black communities in Miami through the center’s community partnerships and hosted focus groups in Haitian Creole or English to better understand what African Americans and Haitians knew about hepatitis B. Their comments were eye-opening: Community members expressed difficulties in going to a doctor, paying for medical care, getting time off from work — even a distrust of the health care system. There were many misconceptions about the disease, as well.

Addressing these barriers is essential, because liver cancer is expected to surpass colorectal, prostate and breast cancer as the third-leading cause of cancer deaths in the next decade.

Of course, it’s not just liver cancer that affects minorities unevenly. African American men have a higher risk of prostate cancer, which prompted Brandon Mahal, M.D., to devote his research to finding out more about the genomics of Black men’s tumors and the use of precision medicine to target those tumors.

As assistant director of outreach and engagement at Sylvester, Dr. Mahal wants to identify the reasons for this disparity. He thinks social structure barriers instead of genomic dissimilarities may explain some of the difference in treatment results. Existing research has already shown that African American men who have tumor characteristics similar to those of their white counterparts can have comparable outcomes if they receive the appropriate therapy.

Proper Care for All Patients

his, he adds, underscores the importance of access to care for all patients. Growing up in a poor community in central California, Dr. Mahal witnessed how “cancer was universally fatal. It was a death sentence,” he recalled. “But as I got into my medical training, I saw where many cancers have excellent therapies — if only patients can receive them.”

his, he adds, underscores the importance of access to care for all patients. Growing up in a poor community in central California, Dr. Mahal witnessed how “cancer was universally fatal. It was a death sentence,” he recalled. “But as I got into my medical training, I saw where many cancers have excellent therapies — if only patients can receive them.”

At the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology this past summer, Dr. Mahal and his co-authors presented a study that showed Black men were less likely to be genetically profiled early. They were also less likely to be part of clinical trials. Both facts directly affect targeted treatment and outcome.

“I was drawn to Sylvester in part because of its community-oriented approach to looking at and solving health care disparity,” he said. “Other institutions are just now recognizing this, but here it has been core to the mission. Sylvester Director Stephen Nimer has a firm and thorough understanding of how important this is.”

On another front, the urgency to understand why Hispanic patients have a higher death rate for some cancers and poorer health-related quality of life has inspired Sylvester researchers to team up with the Mays Cancer Center in San Antonio. The joint study, Avanzando Caminos (Leading Pathways): The Hispanic/Latino Cancer Survivorship Study, is funded by a $9.8 million, six-year grant from the National Cancer Institute. Though there have been other studies on Hispanic survivorship, this will be the largest ever. About 3,000 participants from the two sites will be followed over a period of three years, with groups of survivors joining the study at staggered times.

“We have designed this study to better understand what factors promote better outcomes in diverse Hispanic populations in two large Hispanic communities in the U.S.,” said psychologist Frank Penedo, Ph.D., the director of Sylvester’s cancer survivorship program and associate director for Cancer Survivorship and Translational Behavioral Sciences. “Having a better understanding of how specific sociocultural, psychosocial and biological pathways contribute to worse outcomes will help develop and implement secondary and tertiary prevention efforts.”

The information gleaned from the study will help inform future Hispanic cancer patients how to recover better — and reduce the chances of cancer coming back. Already, experts expect a 142% increase in cancer cases among Latinos by 2030.

Achieving health equity will require an investment in time, talent and money over the long run, but Sylvester researchers believe it can be done.

“We are obligated,” said Dr. Kobetz, “to ask the question, Why is this happening? But to go beyond that, we must also ask, What can we do about it?”![]()