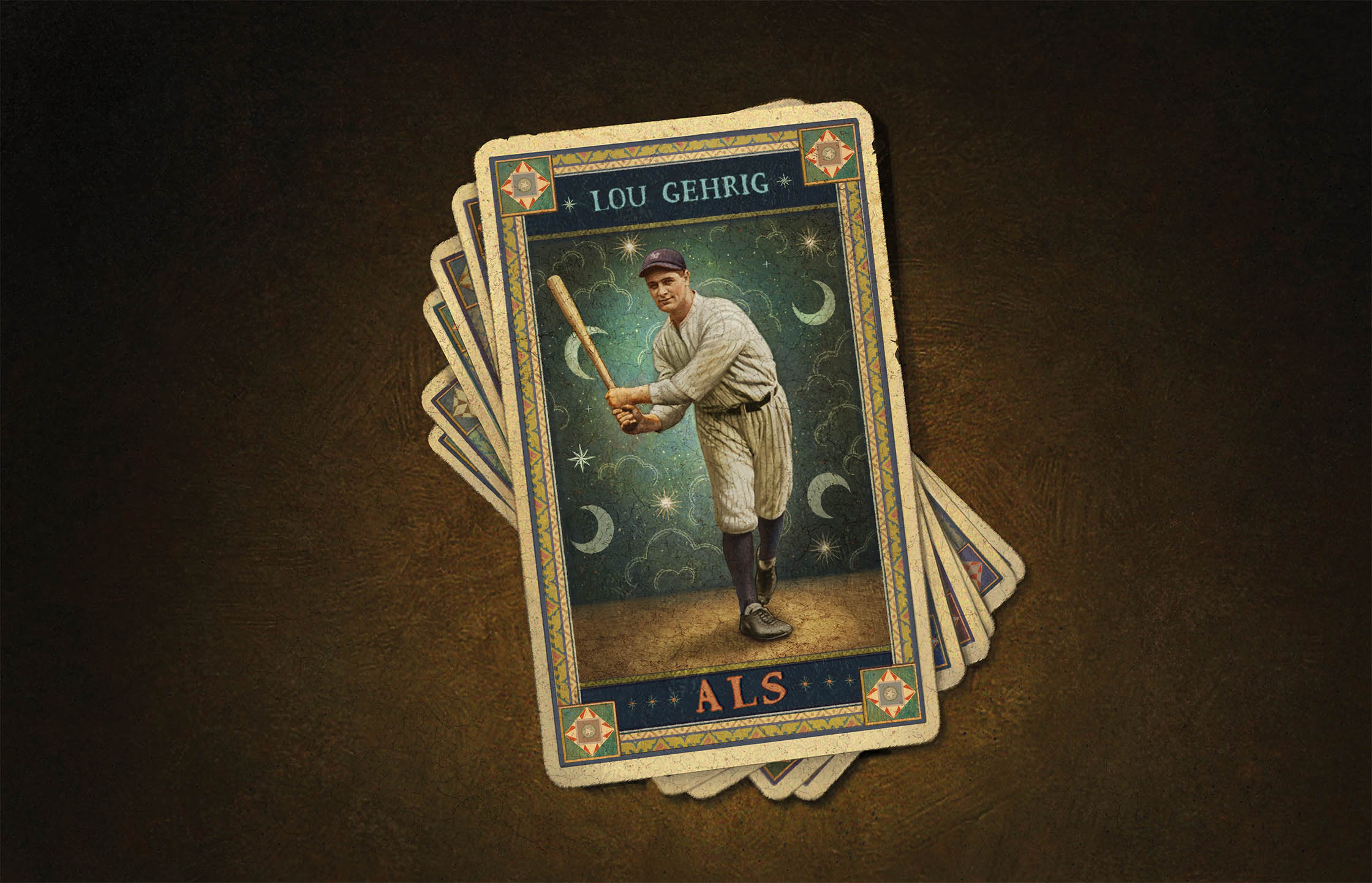

Dealing ALS a New Hand

Research reveals clues that may enable treatment even before symptoms show

By Josh Baxt

Illustration by Daniel Craig

W

hat if you could detect a disease before its devastating symptoms began to present? Would that information help scientists find treatments? Could it prevent a fatal illness? What might this data tell us about the causes of the disease?

Those are some of the questions Michael Benatar, M.D., Ph.D., executive director of the ALS Center at the Miller School of Medicine, began to ask himself as a young researcher in the field of neurodegenerative disease. Those same questions continue to inform his work today as chief of the Neuromuscular Division and the Walter Bradley Chair in ALS Research.

“Our premise is that if we can intervene early with ALS, we can treat it before the onset of symptoms and perhaps delay or prevent it,” Dr. Benatar said. “We know from other medical fields that the best treatment is often the earliest treatment.”

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, for the famous baseball player who died from it — is a progressive neurological disorder affecting the brain and spinal cord nerve cells that control voluntary movement. It is invariably fatal, with an average life expectancy of about three to five years once symptoms present. Though ALS was first identified in the 1860s, its underlying causes are not fully understood, and a cure remains elusive. It is considered a rare disease, with about 7,000 new patients diagnosed every year in the United States and an estimated 30,000 Americans currently living with it, according to The ALS Association. Age at onset is usually between 40 and 70 years, but ALS can strike at any age.

A Difficult Disease to Study

Like other neurodegenerative diseases, ALS is particularly difficult to study. Unlike with most cancers, for example, where scientists can often access and study the tumor, researchers plumbing the mysteries of ALS must investigate it in an indirect way, since one can’t readily biopsy the brain or spinal cord.

Dr. Benatar’s research has drawn international attention for its potential to both identify and treat ALS. He has focused a large part of his work on clinically presymptomatic individuals who are carriers of genetic variants that put them at significantly elevated risk. Dr. Benatar said he studies this population because it provides a unique opportunity to investigate the underlying biology of the disease before it manifests itself, potentially offering windows into early intervention therapies.

“Our premise is that if we can intervene early with ALS, we can treat it before the onset of symptoms and perhaps delay or prevent it.”

One of his ongoing clinical trials, known as ATLAS, seeks to evaluate whether the investigational drug tofersen can delay or slow the onset of ALS in presymptomatic individuals with a highly penetrant SOD1 mutation associated with rapidly progressive disease. Sponsored by the biotechnology company Biogen and designed by Dr. Benatar in collaboration with Biogen, this trial could begin to answer the crucial questions of who should get presymptomatic treatment and when.

ATLAS is the first interventional trial for presymptomatic ALS. Though genetic ALS accounts for only 10% to 15% of all cases and SOD1 mutations are responsible for 20% of those, Dr. Benatar believes that proof of principle, through ATLAS, of the critical need for early intervention could have wide-ranging implications for genetic and nongenetic forms of ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases.

ATLAS is based in part on work conducted by Dr. Benatar and Joanne Wuu, Sc.M., research associate professor of neurology and associate director of research at the ALS Center. Through their ongoing Pre-fALS (presymptomatic familial ALS) study, they have been studying presymptomatic gene mutation carriers for about 15 years. A critical breakthrough came in 2017, when they discovered that levels of a protein biomarker in the blood — neurofilament light (NfL) — are elevated six to 12 months before the actual onset of symptoms. In subsequent work, they found that in individuals with certain gene mutations, NfL elevation may appear years before symptom onset.

A Powerful Clinical Detection Tool

“Our ability to detect neurofilament elevation presymptomatically, and to use this as a tool to predict when people will develop overt clinical manifestations of the disease, is a game-changer,” Dr. Benatar explained. “It empowers us to intervene early and potentially to prevent the clinical onset of the disease.”

The international multisite ATLAS is currently enrolling participants. The researchers hope to track NfL levels in 150 presymptomatic SOD1 gene mutation carriers. When a participant’s NfL levels increase but no symptoms have appeared, the individual will be randomly assigned to receive either tofersen or a placebo. If clinical symptoms of ALS do subsequently appear, the placebo group will switch to receiving tofersen. (So far, Biogen’s tofersen trials have had mixed results. Nonetheless, the drug does reduce NfL levels, and patients who have been taking it for a year, compared to those who have been only taking it for six months, show better clinical outcomes.

Trained in neurology at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and at Harvard, and in molecular neuroscience while a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, Dr. Benatar was the inaugural recipient of The ALS Association’s TREAT ALS Clinical Research Fellowship in 2006. He has since established himself as a thought leader in the field. In addition to defining the field of presymptomatic ALS and championing the idea of ALS prevention long before it became popular, he has challenged existing paradigms for preclinical therapeutic studies, shaped how the field conceptualizes and uses biomarkers for therapy development, and advocated for the use of enrichment strategies in ALS trial design.

Through data generated by the NIH-funded CReATe Consortium that he leads, Dr. Benatar and colleagues have demonstrated the value of neurofilaments as drug development tools, highlighting the superior clinical utility of NfL over the phosphorylated form of neurofilament heavy chain, or pNfH, that had been the overwhelming focus in the field.

Most recently, Dr. Benatar and Wuu have defined a new clinical syndrome that they have termed “mild motor impairment,” or MMI. MMI represents a prodromal phase of disease that is detectable and precedes clinically manifest disease. It is part of the disease course not only for mutation carriers who later develop genetic forms of ALS, but also, the researchers believe, for patients with nongenetic forms of ALS (known as sporadic ALS). This critical insight may empower the study of presymptomatic disease in the more common sporadic ALS, and potentially opens the door to earlier treatment and perhaps even prevention in all ALS.

Dr. Benatar is cautiously optimistic.

“A presymptomatic treatment for even a small subset of individuals would represent a giant leap forward for the field,” he said. “The emerging insights could be transformative for how we approach therapy development for all forms of ALS.” ![]()