A yoga routine that is challenging both physically and mentally can improve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and doctors can use noninvasive imaging of the retina to track a participant’s progress, according to new collaborative studies by University of Miami researchers.

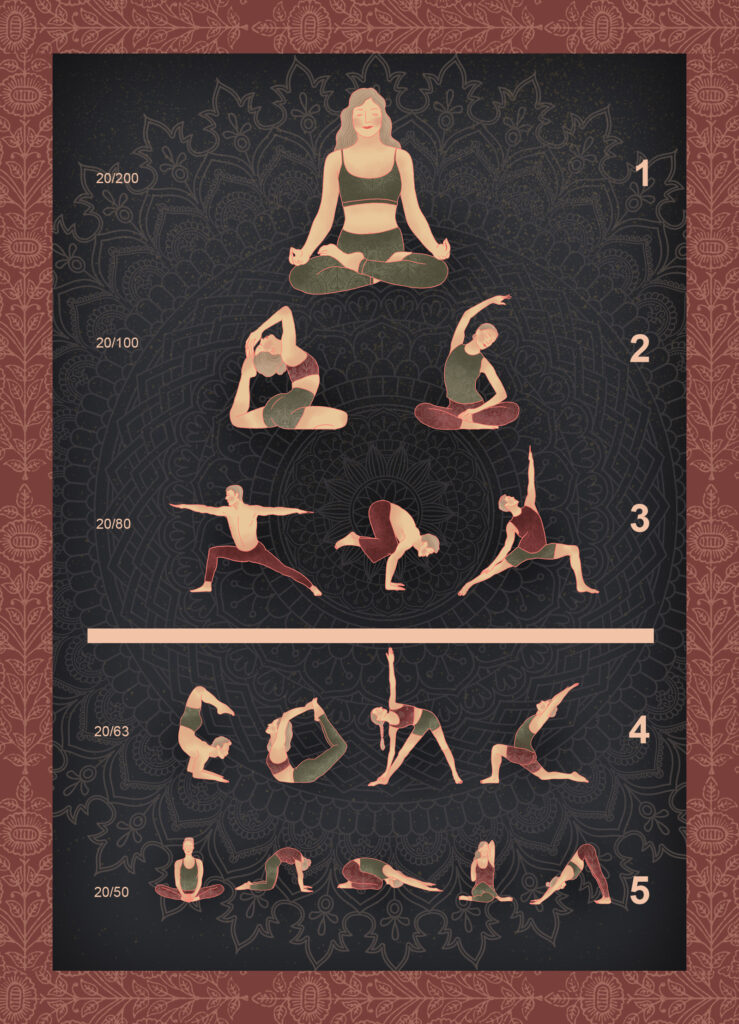

Several years ago, Joseph F. Signorile, Ph.D., professor of exercise physiology and neuromuscular research in the Department of Kinesiology and Sport Sciences, and his team began developing YogaCue, a program that combines standard yoga poses with interval training and cognitive challenges.

“Our concept was that we knew high-intensity exercise had a positive impact on cognition,” he said. “We also knew that providing a mental challenge would have a positive impact on cognition. So, we put the two together and made a combination program.”

Early patients experienced improvements in physical and mental symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but Dr. Signorile wondered if there was a way to explore exactly how the brain was changing in response to the exercise. The research, which was partially funded by the Miller School, demonstrated that noninvasive eye imaging techniques could give scientists clues as to how people’s brains are responding to the program.

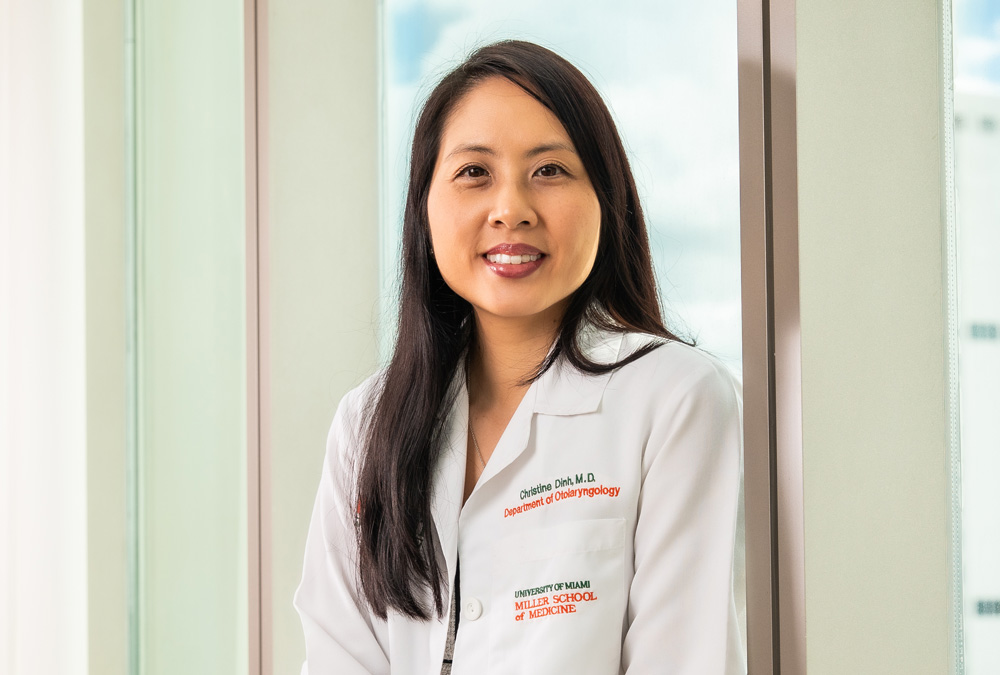

Diane Zheng, Ph.D. ’19, M.S., a research assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Miller School, spent years researching the connection between vision and overall health and quality of life. But when she decided to study the specific connection between sight and cognition, she found that the two were very closely related, a finding that seemed to surprise the field.

When the paper that described that connection was published in JAMA Ophthalmology in 2018, “it got a lot of attention,” she said.

Since then, Dr. Zheng and her team have published several more studies clarifying the relationship and providing evidence of the importance of maintaining visual health throughout life.

In both cases, the researchers point out that monitoring changes in vision and eye health can help doctors understand how well an aging individual’s brain is functioning.

The rate of vision loss is related to the rate of cognitive decline.

The Eye as a Window to the Brain

Dr. Signorile teamed up with Jianhua (Jay) Wang, M.D., Ph.D., M.S., professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

“We have a large research group at Bascom Palmer where ophthalmologists and neurologists work together. We focus on the eye as a window to the brain, or systemic disease, like diabetes and Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Wang said. “The collaboration is unique. No other lab can do the full spectrum of eye imaging like we do here.”

He and his team set out to develop a way to measure the changes in a person’s brain in a way that was not only inexpensive but also could be done noninvasively during a routine doctor’s appointment.

Retinal tissue, Dr. Wang explained, is not just connected to the brain, it is a part of the brain. “If we can visualize how blood flow is changing here, we can get an idea of how the brain is responding to exercise without heavy-duty, expensive brain scans,” he said.

In two small studies published during the spring of 2025, the team found that changes in blood flow and an density of capillaries in the retina, were correlated with tests on cognitive performance and severity of disease.

The workout is intense, Dr. Signorile explained. “It is really an interval training program, and the intensity goes up throughout. The stimuli for increased angiogenesis, in other words, the production of more blood vessels, and synaptogenesis — new connections being formed between brain cells — happens due to increases in aerobic and neuromuscular performance.”

Visual and Cognitive Decline Go Hand in Hand

In the 2018 study, Dr. Zheng and her team examined visual acuity and cognitive function for 2,520 individuals between the ages of 65 and 84. Subjects were tested up to four times over the course of eight years. The results showed that visual and cognitive decline seemed to go hand in hand. The rate of vision loss is related to the rate of cognitive decline and further analysis suggested that vision loss has a stronger effect on cognition than the other way around.

Dr. Zheng’s most recent study, published in June in the American Journal of Ophthalmology, started to tease apart these different mechanisms in participants across a range of ages and genders. For example, vision loss can make it harder to participate in certain activities and socialize. That can cause people to become isolated, which leads to a lack of brain stimulation and subsequent cognitive decline, a sequence of events more common among older men in the study. On the other hand, vision loss contributes to cognitive decline by exacerbating depressive symptoms, a pathway more common in middle-aged women.

The most important takeaway from her work, she said, is “as you or your family members get older, I urge you to take care of your senses and have yearly vision and hearing examinations. These senses have an impact not only on your quality of life but also in maintaining your cognition.”

“We knew high-intensity exercise had a positive impact on cognition.”

The Future of YogaCue

One of the main priorities for Dr. Signorile and Dr. Wang is making the intervention and the imaging techniques as accessible as possible.

“Yoga is a very popular exercise, so if we can modify it in order to positively affect cognitive performance as well as physical performance, then that’s very, very meaningful,” Dr. Signorile said. “And it doesn’t require a lot of equipment or anything else. It’s accessible.”

Dr. Wang added that once researchers can confirm the ways in which capillary networks in the eye change in response to disease and exercise, he hopes ophthalmologists will be empowered to use existing eye imaging technology to better understand diseases such as Parkinson’s.

The team is getting positive feedback from practitioners throughout the country, Dr. Signorile said, but they still need to do studies with many more participants to validate the finding.

“I cannot do my part alone, and Dr. Signorile cannot do his part alone,” Dr. Wang said. “We plan to conduct a large-scale study to address the questions we haven’t answered yet.”